Journey to Liberation: Understanding the Qualities of a Jivanmukta

This blog shares my experience of a Vedantic session. Please excuse any errors or misunderstandings in my depiction or interpretation

Last week I attended a beautiful Vedantic discourse and I'm still processing the profound insights that were shared. The session was organized by the Aham Brahmaasmi Foundation® (A Unit of Dakshinamnaya Sri Sharada Peetham, Sringeri) and was delivered by Sri Adithyananda Saraswati, Chinmaya Mission, Mandya. What started as a simple discussion about spiritual concepts turned into a deep exploration of what it truly means to live liberated while still being fully human.

The discussion centered around the qualities of a Jivanmukta—what does it truly mean to be liberated while living? The term "Jivanmukta" perfectly embodies this paradox: someone who exists in the world yet remains entirely free from its binding influences. Liberation from what, though? This essential question led us to explore a deeper understanding.

Liberation isn’t about escaping life itself but overcoming the deep ignorance of our true nature that keeps us stuck in endless cycles of suffering and searching. Swamiji highlighted that every human being, without exception, seeks happiness and avoids pain. This universal drive shapes all our actions, relationships, successes, and even spiritual pursuits. Yet, no matter how much we achieve or strive, lasting fulfillment often slips away like water through our fingers.

Then, Swamiji shares a profound teaching often emphasized by Adi Shankaracharya:

"अप्राप्तस्य प्राप्तिर्न प्राप्तस्य ज्ञानम्"

We are constantly trying to "get what we do not have" when the real need is to "know what we already have." What we seek outside ourselves - peace, joy, completeness, love - is already our essential nature, waiting to be recognized rather than acquired.

Even the Upanishads mention that liberation comes through knowledge, but not the intellectual kind we're accustomed to in schools and universities. The concept of

"ज्ञानादेव कैवल्यम्"

(Jñānādeva Kaivalyam) liberation through knowledge - represents this transformative understanding about our own true nature. When this knowledge dawns, it doesn't add anything new to us - rather, it removes the false beliefs and identifications that have been covering our inherent wholeness.

Having understood the meaning of Jivan Mukta, Swamiji elaborates on the different names associated with a Jivan Mukta. They are known as Sthitha Pragya – someone whose wisdom remains steady regardless of external events. They are true Sannyasis – not because they have renounced the world or their duties, but because they have let go of the ego's sense of ownership. They can fully participate in family, work, and society while staying inwardly free. They are Yogis in the truest sense – having realized their oneness with all existence, seeing themselves in everyone and everyone in themselves.

Now, getting to the main question, how do these mahatmas navigate their lives within society? Arjuna's questions to Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita reflect our natural curiosity about how such enlightened beings live in the everyday world.

अर्जुन उवाच

स्थितप्रज्ञस्य का भाषा समाधिस्थस्य केशव।

स्थितधीः किं प्रभाषेत किमासीत व्रजेत किम्॥२.५४॥

"O Keshava, what is the description of him who has steady wisdom and who is merged in the superconscious state? How does one of steady wisdom speak, how does he sit, how does he walk?"

The answers reveal beings who possess a remarkable equanimity. They remain unshaken by success or failure, praise or blame, gain or loss. Their peace doesn't depend on external conditions being favorable because they've found their source of fulfillment within their own being. When praised, they don't become inflated with pride. When criticized, they don't become defensive or hurt. They respond appropriately to each situation while remaining centered in their true Self.

What makes these teachings particularly valuable is that they serve a dual purpose. On one level, they describe the natural state of the awakened being, satisfying our curiosity about what liberation actually looks like. But more importantly, they provide a detailed roadmap for seekers still on the path. Each quality of the Jivanmukta becomes a practice, a way of training our minds and hearts to gradually align with our true nature.

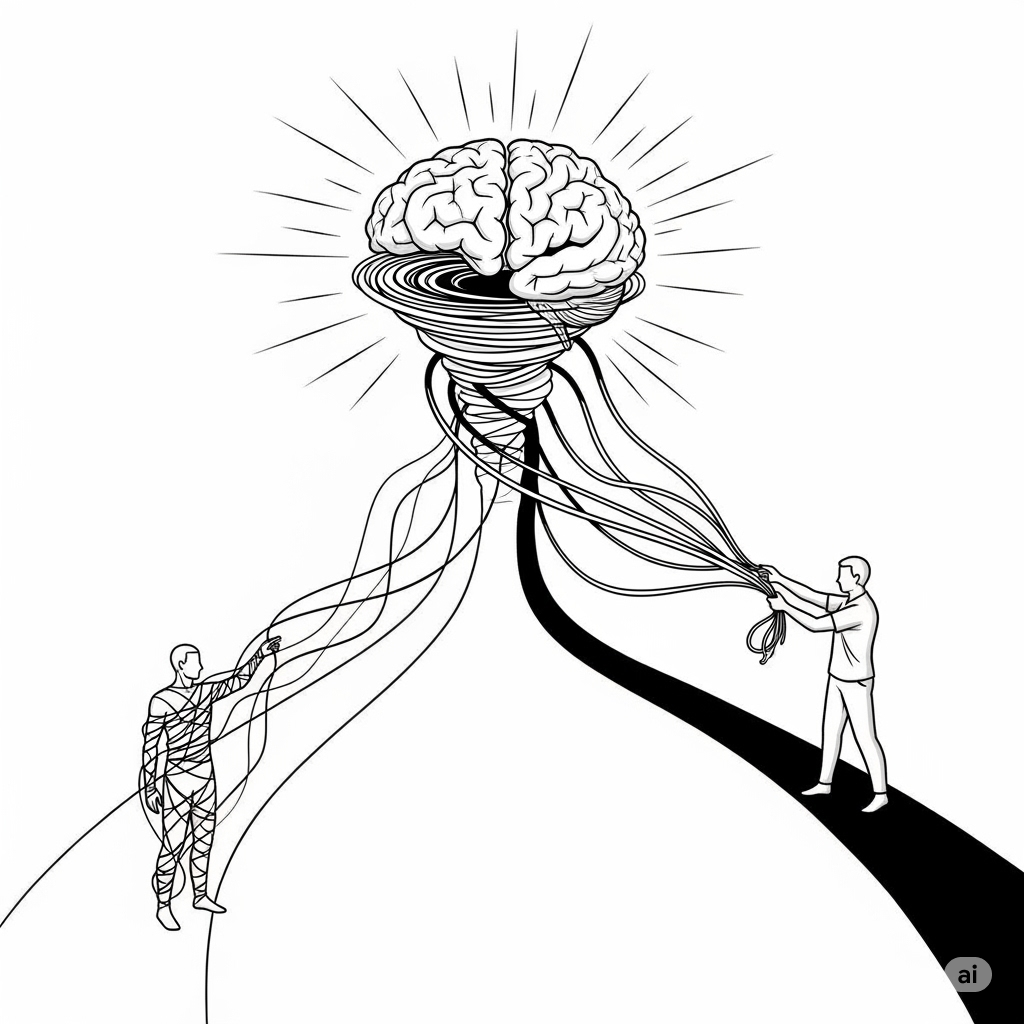

But this raises the practical question that every sincere seeker faces: how does one actually walk this path? The obvious answer - simply drop all desires and attachments - proves frustratingly inadequate when we try to implement it. Our conditioning runs incredibly deep, shaped by countless lifetimes of habits and countless years of reinforcement in this lifetime. Forceful suppression of desires often creates more problems than it solves, leading to inner conflict and eventual explosive reactions.

This is where understanding the mind's nature becomes absolutely crucial for any serious spiritual aspirant. The mind has a fundamental characteristic that we can work with rather than against: it naturally becomes attached to whatever we do repeatedly and consistently. This principle works both for and against us, depending on how consciously we apply it.

If we constantly engage in worry, criticism, gossip, or complaint, the mind develops deep grooves in these directions. Like water flowing down a hillside, our thoughts automatically follow these well-worn channels. But here's the beautiful opportunity: if we consistently engage in uplifting activities contemplation, service, study of scriptures, devotional practices - the mind gradually shifts toward these more positive patterns.

A beautiful metaphor was shared by Swamiji that illuminated the practical path forward for anyone feeling overwhelmed by their mental conditioning. Imagine you have a glass of water that's so salty it's completely undrinkable. Add five glasses of sweet water to the mixture. The salt doesn't disappear, but it becomes negligible in the sweetened mixture. The water is now not only drinkable but actually pleasant

This metaphor reveals a profound truth about spiritual transformation. Instead of fighting our conditioned patterns and negative tendencies head-on, we gradually add more and more positive qualities until they transform our entire inner landscape. We don't have to achieve perfection right away or completely rid ourselves of ego and desire. All we need is to steadily add "sweet water" – the practices, perspectives, and activities recommended by the shastras.

Swamiji shared a meaningful teaching from his guru: "Take God's name whenever you walk, so your mind stays focused." This simple practice helps keep the mind occupied with something uplifting and positive, preventing it from drifting into worries, overthinking, or judgmental thoughts about others.

This illustrates a fundamental truth about spiritual practice: with the mind, there are only two possibilities - either we direct it consciously toward positive objects, or it directs us unconsciously toward whatever has captured its attention. There's no neutral ground where the mind simply sits quietly without any object of focus.

The great spiritual luminaries throughout history understood this principle deeply and kept their minds constantly engaged in uplifting activities. They practiced nama japa - the repetition of divine names that gradually purifies consciousness. They wrote extensively about spiritual topics, using intellectual engagement as a form of meditation. They sang devotional songs and hymns, using music and poetry to elevate their emotional nature. These weren't mere religious observances or cultural traditions, but sophisticated technologies for training attention and cultivating positive mental states.

As Swamiji explained, the mind naturally falls silent in only two states: deep sleep and death. In both instances, the thought process halts, but these are not conscious experiences we can learn from or intentionally recreate. This reminds us to avoid being harsh or forceful with our own thoughts and emotions.

The key insight is that each person must find approaches that work for their unique temperament and circumstances. What calms one person's mind might actually agitate another's. A devotional person might find peace in singing bhajans, while an intellectual type might prefer studying scriptures. Someone with an active temperament might find service more suitable than sitting meditation. The art of spiritual practice lies in discovering our own most effective methods for cultivating inner peace and clarity.

The discussion became more engaging as we delved into Vidyaranya's insightful classification of the four types of sannyasis in his renowned work "Jivanmukti Viveka." This ancient text offers a nuanced perspective on how various temperaments and levels of spiritual realization pursue liberation. Swamiji briefly outlined the meaning of each type.

Kutichaka - These practitioners maintain a simple dwelling while continuing to receive sustenance from their family members, representing an early stage of renunciation.

Bahudaka - This category includes those who require frequent ritual purification and therefore establish residence near water sources such as rivers, though they still depend on family for nourishment.

Hamsa - These individuals have embraced complete wandering asceticism, sustaining themselves entirely through alms collection rather than family support.

Paramhamsa (Vividisha) - This classification encompasses serious students of spiritual texts who actively pursue scriptural knowledge and understanding as their primary focus.

Paramhamsa (Vidwat) - These are accomplished scholars who have mastered the sacred scriptures and represent the learned class among advanced practitioners.

Swamiji describes the qualities of a Jivan Mukta, highlighting that their actions may seem unconventional or puzzling because they align with deep spiritual principles rather than social norms or traditional rules. They might display childlike innocence, act like a madman ignoring societal conventions, or embody the wisdom of a sage, depending on what each situation demands.

Krishna's teachings about the field and its knower provided another crucial framework for understanding how the Jivanmukta relates to their embodied existence. The kshetra (field) includes the body, mind, emotions, thoughts, and all experiences - the entire arena where life's drama unfolds. But our true identity is not the field itself; we are the kshetrajna - the conscious awareness that knows and witnesses the field.

This distinction is absolutely transformative when properly understood. Instead of being lost in the content of our experiences - whether pleasant or unpleasant - we learn to rest in the awareness that witnesses all experiences without being affected by them. The body may feel pain or pleasure, the mind may experience thoughts of joy or sorrow, but the witness-consciousness remains perpetually free and untouched.

This understanding naturally leads to the practice of "असङ्गोऽहम्" (Asangoham) - "I am unattached." One of the most striking qualities of the Jivanmukta that emerged from our discussion is their unwavering equanimity in all circumstances. Whether surrounded by admirers singing their praises or tormented by critics trying to defame them, their inner state remains completely unchanged. This remarkable steadiness doesn't come from emotional numbness or indifference, but from profound understanding.

In their daily activities, the ego's constant internal commentary gradually fades away. They eat when hungry, sleep when tired, work when needed, and relate to others when appropriate - but without the mental noise of "I am doing this," "this belongs to me," or "I should be getting credit for this." Life becomes effortless and natural, like a river flowing smoothly toward the sea without any sense of strain or struggle.

Perhaps most beautifully, they begin to perceive the same divine essence in everyone they encounter - whether parent or child, friend or stranger, supporter or critic. This isn't a philosophical concept they've intellectually adopted, but a living reality they experience moment by moment. The artificial barriers between self and other dissolve in the recognition of fundamental unity, leading to spontaneous compassion and unconditional love.

For those still walking the path toward this realization, practical wisdom emerged about managing the inevitable mental disturbances that arise in daily life. Just as we wouldn't deliberately reach out and touch fire because we know it will burn us, we need not expose ourselves unnecessarily to conditions and influences that agitate the mind, especially in the early stages of practice.

This doesn't mean running away from all challenges or responsibilities, but rather developing discrimination about when engagement is helpful and when distance is wiser. The great Marathi saint Tukaram captured this approach beautifully in his profound verse-

"जे होईल ते पहावे"

(Je hoyeel te pahaave) - "Whatever happens, let me witness it." These simple words contain the entire essence of spiritual practice condensed into practical guidance. Instead of being caught up in life's inevitable dramas - the successes and failures, the joys and sorrows, the meetings and partings - we learn to observe everything with conscious, loving awareness.

This points toward perhaps the most transformative practice available to any sincere seeker: learning to become the conscious witness (Sakshi) of our own life. Instead of being completely lost in our personal story - "my problems," "my achievements," "my relationships," "my spiritual progress" - we gradually learn to step back and observe the entire unfolding drama with loving, detached awareness.

This shift in identity from participant to witness represents the very heart of spiritual transformation. We continue to live fully, love deeply, work diligently, and care genuinely about others, but we do so from a place of inner freedom rather than compulsive attachment. We engage with life's joys and sorrows, but we're no longer enslaved by them.

The Jivanmukta demonstrates for us that it's completely possible to be fully human while remaining utterly free. They show us that we don't have to choose between being loving and being detached, between being engaged and being peaceful, between caring about the world and being established in transcendence.

In this profound understanding, liberation reveals itself not as an escape from life but as the most complete and fulfilling way of living possible - deeply engaged yet unattached, genuinely caring yet non-possessive, fully active yet perfectly peaceful. The path opens before each of us, inviting us to discover and embody what we have always been but have somehow temporarily forgotten.

The beauty of this teaching is that it doesn't require us to become someone else or achieve some impossible standard of perfection. It simply asks us to gradually remove the layers of false identification and conditioning that obscure our natural state of freedom, love, and peace. Like an artist carefully cleaning an ancient painting to reveal the masterpiece that was always there, we patiently work to uncover the liberated being that is our true nature.

Hari Om!

-acintya

Comments

Post a Comment